Cancer. It’s the scariest six-letter word in the dictionary.

That’s because it’s the world’s number one killer – and can affect anyone, regardless of age, sex, race or geography.

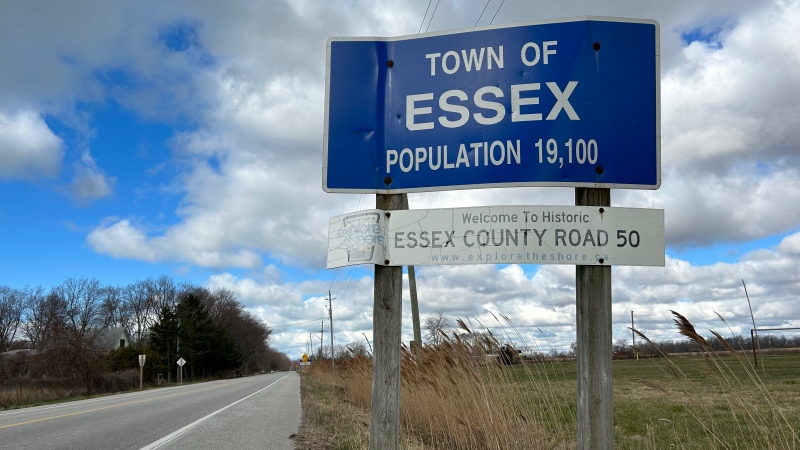

And Windsor resident Diane Marley didn’t see it coming.

"It's just one of those things I thought it's never going to be me," says Marley, who was diagnosed in 2013 with invasive ductal carcinoma, a form of breast cancer.

"I was frightened,” she recalls. “The first thing I thought of was people die of cancer. I don't want to die."

In Ontario alone, 30,000 people died of cancer in 2017. That same year, more than 80,000 new cases of the disease were diagnosed.

Marley didn’t want to be a statistic. She wanted to beat cancer and be part of a different group: cancer survivor.

"I'm going to fight this thing to the bitter end," she recalls saying at the time.

Marley’s confidence was buoyed by the launch of the Windsor Cancer Research Group, which started in 2012 as a core group of doctors and researchers looking at cancer through a multi-disciplinary lens.

Lisa Porter, a renowned, award winning cell biologist at the University of Windsor, co-founded the group.

“We’re bringing people from all aspects of the cancer spectrum together, and putting all of these ideas together and how we solve the whole continuum of what people are going through," says Porter.

Windsor oncologist and WCRG clinical director, Dr. Caroline Hamm, believes the best approach to finding a cure for cancer is to have as many people from as many disciplines as possible working together, collaborating their research.

She says that’s the best formula for getting access to grants and growing the quantity and quality of the local research community, to tackle the problem together.

"Unless we do the research and build towards that, take baby steps toward that magic pill, then we're never going to get there,” Hamm says. “So we need to always be challenging what the current best is, with the other, new best."

Good research doesn’t come cheap

Research takes time, patience and of course, money. In Canada, cancer research is funded by government, the private sector and charities. Over the past decade, between $500 million and $600 million has been spent on research in Canada each year, with the bulk of funding coming from government.

But Dr. Lisa Porter says it’s easier to get grants and funding when you have an established team of researchers with a track record of successful research projects.

"We've more than tripled the grants being submitted and funded here at the University of Windsor because of that kind of thing,” she says. “That’s because we're putting people together to really evolve the way we're thinking and doing things."

But it’s not just national and provincial money filtering down. Local fundraising also plays a big role.

"People say this all the time: 'Someone else can do it.' we can say that about almost anything else. You can't do that,” says Houida Kassem, the executive director of the Windsor Cancer Centre Foundation. “We have to help each other locally."

The Seeds4Hope program, funded through the Windsor Cancer Centre Foundation has provided 30 grants to local researchers over the past decade, valued at $2.2 million.

"Every dollar raised stays local. That's our mandate,” says Kassem. “The biggest partner is the community because they also show us that they care.”

“They give us hope. They reach into their pockets and say, here you go, here's some money because we want to make a difference in the community,” Kassem says.

Lab and clinical researchers working together

Dr. Porter believes that research can begin at the lab bench and the bedside, based on observations of cells and patients, respectively. Communicating those observations and results in either direction underlines the importance of collaboration, she says.

A study that’s been taking place in Windsor over the past number of years serves as a great example. It was based on a patient challenging Dr. Hamm about her treatment plan during an appointment.

The result? Dr. Hamm and Dr. Porter landed a $70,000 Seeds4Hope grant in 2010 to study triple negative breast cancer patients on a standard dose drug regiment, in combination with another drug, Carboplatin.

90 local patients were treated with the new protocol, and the investigators found decreased relapse rates for patients with stage one and two of the disease. The clinical trial also identified potential drivers of relapse.

Local patients were able to take part in that study thanks to geography – at a time when people in other parts of Canada couldn’t.

"It's kind of cool that Windsor patients actually got all this treatment five years earlier than everyone else in the world and are getting the benefit earlier,” says Dr. Hamm.

Diane Marley is one of them.

"If it wasn't for him starting this seeds for hope and these grants, I probably would not be here," Marley says.

She was happy to volunteer for the clinical trial – if not for her own sake, then for someone else’s.

"I feel like all the drugs that I had had to be in a trial somewhere previous. So what they're doing for me hopefully will be something that's going to be the answer for somebody else," says Marley.

This research translated into a $765,203 grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, which brought together a team of surgeons, pathologists, oncologists and university professors to study new possible treatment directions. Already, a protein has emerged as a potential new treatment direction.

"It's the hope. It's the hope that the next people going through this will have a better outcome," says Dr. Hamm.

It’s one example of leveraging local resources to attract higher-level government funding, providing for improved breast cancer treatment. With an estimated 10,000 new cases diagnosed in Ontario in 2017, it’s one of the most prevalent forms of cancer – and also one of the most survivable, thanks in part to the fortune being focused on the type of cancer.

Marley is now 53, and is five years post-treatment without a recurrence.

"What if this really is it?” asks Marley. “What if these wonderful people right here in Windsor figure out a way to help people like me that are triple negative cancerous?”

“It gave me a lot of hope."

Is there hope for a cure?

The short answer is yes. After 70 years of research, the cure-rate for some cancers is getting higher, and life expectancies after diagnosis are stretching out. Through research and trials, people are living with cancer longer. Prevention and education also play a large role.

But some cancers continue to puzzle the brightest minds in the world. In 2017, 30,000 Ontarians died from various forms of cancer. Another 80,000 new cases were diagnosed. The quest for a cure persists.

Dr. Porter likes to explain the progression of cancer research with a simple analogy.

“Cancer research is like a wall,” she says. "We have a really strong foundation. Every single time we put a brick in the wall, every time we make things better, it makes somebody out there safer."

And while that wall is getting taller, Porter says some forms of cancer barely have foundations.

"There's never going to be one cure for cancer," says Porter. Her lab colleague, Bre-Anne Fifield, says that’s because the disease is so diverse.

"It's not just one disease, it's really hundreds of different diseases," Fifield says.

But local researchers are motivated, nonetheless. That’s because nearly everyone will be touched by cancer in their lifetimes, whether it’s through a family member, friend or colleague.

"This strikes home,” says John Trant, a biochemist at the University of Windsor. “Almost everybody in there has lost family members to cancer. So we're motivated to do this."

As the team grows and the research evolves, the WCRG also feels more confident that cancer-fighting techniques and life-saving treatments can originate here, instead of somewhere else.

“The woods would be very silent if only the bird with the most beautiful voice sang,” says Dr. Hamm, noting it’s one of her favourite quotes. “We all have to have a part in this fight against cancer."

“One individual mind is not bigger than the overall goal. The goal is big and the problem is big,” says Porter. “We need to come together as a collective. But one of the big things we understand now is what we need to do next."

The WCRG is committed to continuing its mission of collaboration to piece together the world’s most complicated puzzle – all while making important breakthroughs that provide hope to patients here and around the world.

"These researchers are definitely up to the task, there's no doubt about it,” says Marley, a big smile across her face. “Especially here in Windsor.”