Wheatley woman with cancer left without family doctor amid urgent need for medication

Without a family doctor to answer her calls, Susan Way faces the reality of trying to figure out how she can get refills of much-needed medication to relieve the pain of her Stage 4 cancer.

Way is one of many people across Ontario who are unable to secure a family doctor. The 57-year-old said she was first diagnosed with ovarian cancer back in Dec. 2019 before the disease progressed to Stage 4 about a year and a half later.

“I had been getting intermittent pain, which felt like pancreatitis or a gallbladder problem. Eventually, that got intense. I started vomiting and fainting and went to the ER,” said Way.

“A CT scan showed a blockage and a suspicious mass on my ovaries. So the cancer on the ovaries had spread to the intestine … and that was causing the pain.”

Way said, at the time, she was living in Tecumseh where her former family doctor worked. When she and her family moved to Wheatley in Nov. 2021, Way knew her doctor only had a few months left on the job before retirement.

“Our doctor was only doing phone call visits which suited us nicely. We knew he was due to leave in March (2022) sometime. But we didn't want to get deregistered from him until the last minute because then you're left not knowing if you've got someone else,” Way added.

But that concern is now an unfortunate reality for Way and her family.

The Wheatley resident said her search for a family doctor took her to offices in Tecumseh, Leamington, Kingsville and Chatham.

According to Way, Health Care Connect — which helps Ontarians who don’t have a family doctor get matched with one — told her the only doctor in southwestern Ontario they could find for her was in Tecumseh.

Because of familiarity with the region, she said, that option was sufficient for her.

But Way adds that when she went to that office in May to register as a patient, she was told it would take two months to reach the top of the waiting list and another month to get her first appointment.

“I said, Stage 4 cancer, can you move me up the list?” she recalled asking.

“They said, ‘No, everybody's got a problem.’”

For Way, her need to get matched with a family doctor is severe. That’s because she’s experiencing “extreme pain” in her kidney area because the cancer has spread to her adrenal gland.

“I hold onto the Tramadol very tightly, count my pills and try not to use too much because the prescription came from my (previous) family doctor,” Way said, adding she had to call her oncologist multiple times before they allowed her to transfer that prescription.

“Why do I have to beg? I shouldn’t have to. It’s a bit ridiculous.”

According to Way, health professionals have advised her that walk-in clinics will likely not be able to prescribe her the pain medication she needs. Instead, she would need to get them from the emergency room.

“That’s not something I should have to do at this stage.”

Physician shortage

According to the Ontario Medical Association, about one million people in the province do not have access to a primary care physician. The organization adds there are 2.32 physicians for every 1,000 people.

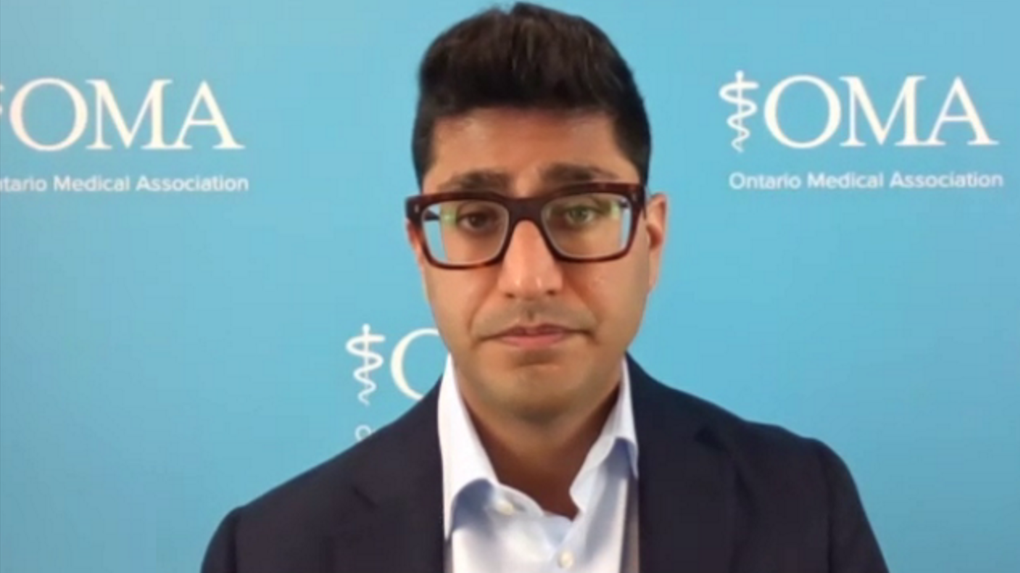

“We know that attraction of medical students and residents into family medicine can be a challenge. We know that remuneration is a challenge,” said OMA president Dr. Adam Kassam, adding there’s a “50-person shortage” of family doctors and specialists specifically in Tecumseh.

Ontario Medical Association president Dr. Adam Kassam says there are about one million Ontarians who still have not been matched with a family doctor. (Sanjay Maru/CTV News)

Ontario Medical Association president Dr. Adam Kassam says there are about one million Ontarians who still have not been matched with a family doctor. (Sanjay Maru/CTV News)

“But ultimately, we also have to recognize that if we want to be able to have a sustainable and robust healthcare system that actually continues to serve the patients in need, we're going to have to invest in primary care, both from a provincial and a federal level.”

On March 28, the OMA ratified a new contract with the province, creating provisions for more family doctors to join Family Health Organizations, groups of physicians who work together to give patients better access to primary care services.

“We believe that family doctors should have the autonomy to choose their practice type, including patient-enrolled models, such as family health organization and family health teams,” said Kassam.

“We know that the previous administration actually kept the ability for new graduates from family medicine residencies to enter these models.”

He hopes the new deal — which also includes a “permanent framework for virtual care by telephone and video” — opens the door for more doctors to pursue family medicine as their specialty.

“There are absolutely services that can be delivered very effectively through virtual means. But there are also other areas of medical care that need to be delivered in person,” he said.

“So we need to figure out a way to shore up and support our existing health, and human resource infrastructure, but also think about the future.”

Way said she’s seen the changes in access to family doctors since she moved to southwestern Ontario about a decade and a half ago.

“When we moved here into the area 15 years ago, there was a shortage of family doctors. Then a few years later, everyone was congratulating themselves because there were plenty. Then, all of a sudden, a number of doctors retire at the same time,” she said.

“It's a mess.”

Way is not the only one in her Wheatley household who urgently needs a family doctor. She said her daughter is in constant need of ADHD medication refills and her husband “can barely walk” because he has stenosis.

By speaking out, Way said her hope is that the health care system can take steps to allow for better access to a family doctor — not just for her family, but for the nearly 3,000 others who live in Wheatley.

“Where are they going to go? They can't go to Amherstburg. There's no doctors there. A doctor in Windsor will have a three or four-month waiting list,” she said.

“Now, it's left them with nothing.”

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

'We're not the bad boy': Charity pushes back on claims made by 101-year-old widow in $40M will dispute

Centenarian Mary McEachern says she knew what her husband wanted when he died. The problem is, his will says otherwise.

Bela Karolyi, gymnastics coach who mentored Nadia Comaneci and courted controversy, dies at 82

Bela Karolyi, the charismatic if polarizing gymnastics coach who turned young women into champions and the United States into an international power, has died. He was 82.

Trump names fossil fuel executive Chris Wright as energy secretary

U.S. President-elect Donald Trump has selected Chris Wright, a campaign donor and fossil fuel executive, to serve as energy secretary in his upcoming, second administration.

'A wake-up call': Union voices safety concerns after student nurse stabbed at Vancouver hospital

The BC Nurses Union is calling for change after a student nurse was stabbed by a patient at Vancouver General Hospital Thursday.

'The Bear' has a mirror image: Chicago crowns lookalike winner for show's star Jeremy Allen White

More than 50 contestants turned out Saturday in a Chicago park to compete in a lookalike contest vying to portray actor Jeremy Allen White, star of the Chicago-based television series 'The Bear.'

NYC politicians call on Whoopi Goldberg to apologize for saying bakery denied order over politics

New York City politicians are calling on Whoopi Goldberg to apologize for suggesting that a local bakery declined a birthday order because of politics.

Montreal city councillors table motion to declare state of emergency on homelessness

A pair of independent Montreal city councillors have tabled a motion to get the city to declare a state of emergency on homelessness next week.

WestJet passengers can submit claims now in $12.5M class-action case over baggage fees

Some travellers who checked baggage on certain WestJet flights between 2014 and 2019 may now claim their share of a class-action settlement approved by the British Columbia Supreme Court last month and valued at $12.5 million.

King Arthur left an ancient trail across Britain. Experts say it offers clues about the truth behind the myth

King Arthur, a figure so imbued with beauty and potential that even across the pond, JFK's presidency was referred to as Camelot — Arthur’s mythical court. But was there a real man behind the myth? Or is he just our platonic ideal of a hero — a respectful king, in today's parlance?