'This city couldn't afford to miss this opportunity': Windsor spends $45 million to acquire Stellantis-LG battery plant properties

Governments of all levels put up hundreds of millions of dollars in taxpayer money as incentive to lure the $5 billion electric vehicle battery plant to Windsor and that includes a sizeable contribution from the city.

In the next two years, a 4.5 million square foot, 45 gigawatt capacity EV battery manufacturing facility will occupy roughly 220 acres of recently acquired lands south of E.C. Row and west of Banwell Road in Windsor, Ont.

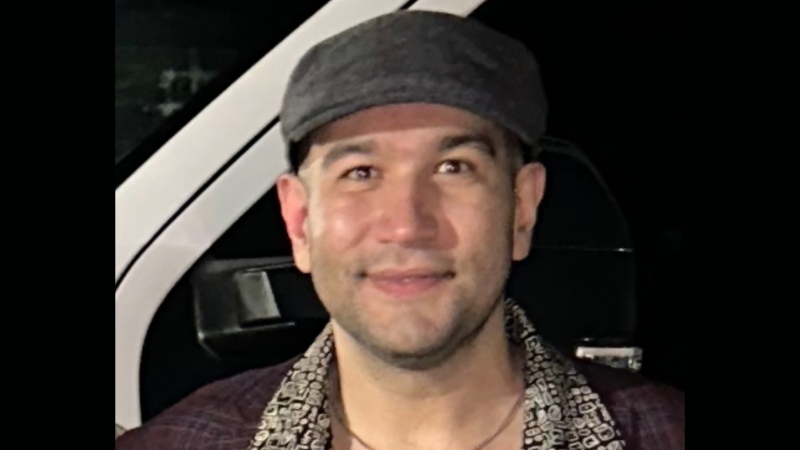

“The facility is quite staggering,” says Stellantis chief operating officer Mark Stewart. “To put it into true Canadian terms, about 112 NHL hockey rinks. That’s a lot, right?”

The feds and province are kicking in “hundreds of millions of dollars” in incentives to land the bid, though neither would disclose the amount for competitive reasons.

But the City of Windsor is opening up about what it took to secure the investment.

When the preferred site was identified, the city went to work acquiring properties into a single parcel.

“We were able to work with all the owners of this land to assemble the land, to make sure there is servicing brought to the land and ensure the company can build this facility on their timeline, which is very, very aggressive,” says Windsor Mayor Drew Dilkens.

All told, Dilkens says the city spent roughly $45 million acquiring the various pieces of land which it will own and lease to the Stellantis-LG Energy Solution joint-venture.

All but one acre is secured, a plot featuring a home at 3455 Banwell Rd. The homeowner wished not to comment Thursday.

But according to city representatives, the city is in active legal negotiations with the residential land-owner and hopes to come to a willing buyer/willing seller conclusion. Failing that, the city has the legislative power to expropriate the land.

“It’s expensive, there’s no doubt about it. And we’ll have to find a way to manage that and we will, and we are,” says Dilkens. “This city couldn’t afford to miss this opportunity.”

The city is also providing a 20-year incremental property tax rebate under the community improvement plan.

Preliminary estimates peg the annual rebate at approximately $3.5 million dollars, which will equate to a $70 million tax holiday after 20 years.

“So for 20 years, it’s a small investment to make to realize year 21 through hopefully year 100 of the investment that will come through property taxes,” the mayor says.

Detroit-based MotorTrend editor Alisa Priddle says some people will call all of these incentives “corporate welfare,” but argues it’s necessary in order to secure big private investments.

“Without incentives we would not have gotten it,” Priddle says.

Priddle had the occasion to interview Stellantis chief executive officer Carlos Tavares in recent weeks, who noted Canada is a higher cost jurisdiction, therefore making it an underdog in landing a battery plant investment. She says other factors, like talent, location and financial incentives made it more plausible.

“Canada has lost out over the years on millions and millions of location choices because they did not play the game or they didn’t play it to the same level,” she says.

“If you don’t buy the ticket you don’t get to play the game,” says Peter Frise, an automotive, mechanical and materials engineering professor at the University of Windsor.

He says luck had nothing to do with landing the manufacturing facility, and notes incentives more than likely helped seal the deal.

“They’re not going to build an infinite number of battery factories and they won’t build it here just because they like the colour of our eyes,” Frise says. “They’ll do it because it’s a good business decision for them. That’s why they did it, period.”

Frise says jurisdictions around the globe compete fiercely to land big investments and says in order to win, governments are expected to sweeten the pot, or let the investment land elsewhere.

“Auto industry co-investments by the public sector always pay off, and they pay off handsomely,” Frise adds. “If you do the math on this, it is inescapable that we will get the money back.”

For example, if the taxpayer-funded investment is about 10 per cent of the $5 billion private investment, that’s $500 million, which Frise says is a fairly typical amount for governments to front.

He did some quick math and estimates an annual payroll at the battery plant will be roughly $300 million.

If about half of that goes back to government coffers in income and property taxes, Frise suggests the investment could pay for itself after less than four years.

“It’s not a bad return on investment and after that, it’s all gravy,” he says, noting the alternative means fewer jobs, fewer future investments and a crippling blow to the future of Canada’s footprint in the auto industry.

“I’m not an economist, but an economist once said if you think public investment in private sector industry is expensive, just try unemployment.”

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

DEVELOPING Person on fire outside Trump's hush money trial rushed away on a stretcher

A person who was on fire in a park outside the New York courthouse where Donald Trump’s hush money trial is taking place has been rushed away on a stretcher.

Mandisa, Grammy award-winning 'American Idol' alum, dead at 47

Soulful gospel artist Mandisa, a Grammy-winning singer who got her start as a contestant on 'American Idol' in 2006, has died, according to a statement on her verified social media. She was 47.

She set out to find a husband in a year. Then she matched with a guy on a dating app on the other side of the world

Scottish comedian Samantha Hannah was working on a comedy show about finding a husband when Toby Hunter came into her life. What happened next surprised them both.

'It could be catastrophic': Woman says natural supplement contained hidden painkiller drug

A Manitoba woman thought she found a miracle natural supplement, but said a hidden ingredient wreaked havoc on her health.

Young people 'tortured' if stolen vehicle operations fail, Montreal police tell MPs

One day after a Montreal police officer fired gunshots at a suspect in a stolen vehicle, senior officers were telling parliamentarians that organized crime groups are recruiting people as young as 15 in the city to steal cars so that they can be shipped overseas.

Vicious attack on a dog ends with charges for northern Ont. suspect

Police in Sault Ste. Marie charged a 22-year-old man with animal cruelty following an attack on a dog Thursday morning.

The Body Shop Canada explores sale as demand outpaces inventory: court filing

The Body Shop Canada is exploring a sale as it struggles to get its hands on enough inventory to keep up with "robust" sales after announcing it would file for creditor protection and close 33 stores.

Tropical fish stolen from Beachburg, Ont. restaurant found and returned

Ontario Provincial Police have landed a suspect following a fishy theft in Beachburg, Ont.

U.S. FAA launches investigation into unauthorized personnel in cockpit of Colorado Rockies flight to Toronto

The U.S.’s Federal Aviation Administration is investigating a video that appears to show unauthorized personnel in the cockpit of a charted Colorado Rockies flight to Toronto.